“[T]he way we structure content says a lot about the values we share.”

One argument I have made for many years is that language matters. In an article for The Think Company, Dave Thomas illustrates clearly why. Using The New York Times as an example, Thomas talks about conventions specifically surrounding gender. If we learn to expect that a woman’s marital status matters and a man’s doesn’t, then we learn that it matters.

This rolls over into every aspect of difference, oppression, diversity, etc. How we present that information, and especially the conventions for the consistency of the presentation, impacts our values and treatment of people. If it becomes convention to include accessibility in website design and writing, that accessibility will no longer illustrate the differences between people with and without impairment, it will just be normal.

Have you ever answered the phone, “Hello,” and the person on the other end says, “Hi, I’m looking for [your name],” and you respond, “This is she (or he, or they).” Probably almost every day, right? Well, every single time I am placed in that structured interaction, I freeze up in the decision moment:

Do I out my pronouns? Do I misgender myself to be safe? Do I break convention and respond in some other way?

A perfectly innocuous moment becomes stressful. It is the same with web content. If the content is structured so that alt text is not included, screen readers can’t identify images for their users. Thus something as innocuous as scrolling through Instagram becomes exclusionary and stressful.

“Currently, content models are primarily seen as mirrors that reflect inherent structures in the world. But if the world is biased or exclusionary, this means our content models will be too.”

Daniel Carter and Carra Martinez compare this content exclusion to roadway designs that limit public transportation in their article for A List Apart. They note that this very physical barrier between parts of the city preventing lower-income traffic is analogous in the way the lack of accessibility measures blocks web content from certain users.

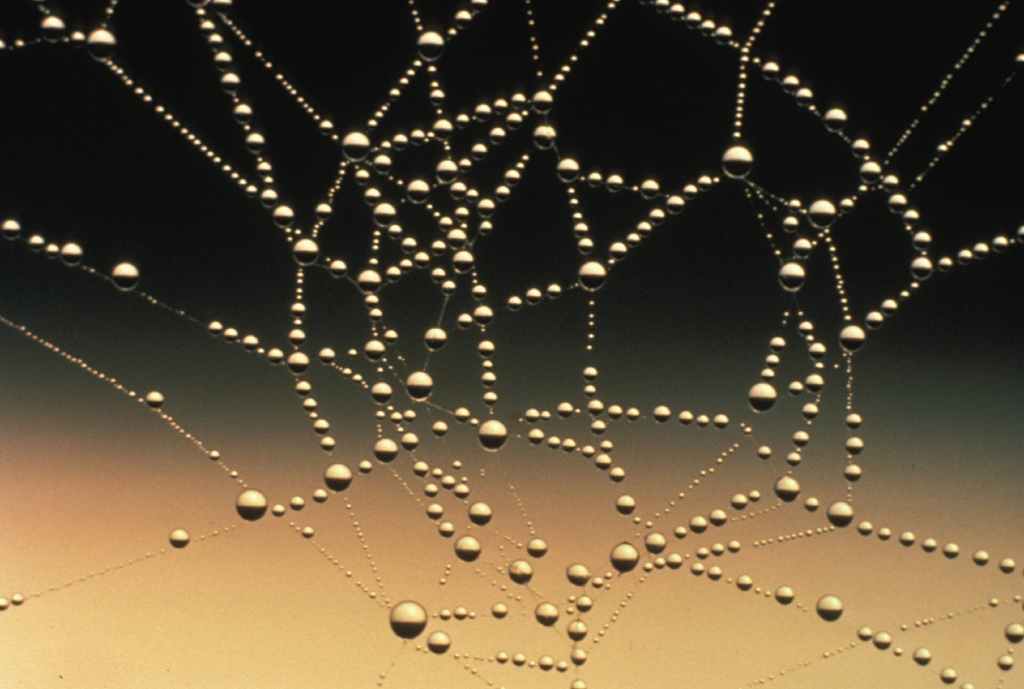

Without this text (which is also embeded in the code of the image), a screen reader would just read “IMG_3918.” Alt text doesn’t have to be a lot. Just that simple sentence allows the reader to also experience the image.

In an article for The New York Times, Meg Miller and Ilaria Parogni provide examples of suitable alt text, and how automatic AI alt text on platforms like Google and Microsoft Word just aren’t enough. This means it is up to us, the content creators and developers, to spend that extra few seconds, or few minutes, to make our content accessible.

Let’s make it the new convention. The new structural expectation.

Leave a comment